Constitutionality vs. Safety

The Legality and Civil Issues of the USA PATRIOT Act

Brian Craigie

Brian Craigie

AP US History

4/1/02

4/1/02

We are an open society, but we are at war. - George W. Bush

Nothing can undo the tragedy that occurred on September 11, 2001. An act of terrorism of that magnitude had never been seen before in our country, and hopefully never will be seen again.

Nothing can undo the tragedy that occurred on September 11, 2001. An act of terrorism of that magnitude had never been seen before in our country, and hopefully never will be seen again.

On October 26, 2001, a mere forty-five days after the attacks on New York and Washington, Congress passed the USA PATRIOT Act. The acronym stands for Uniting and Strengthening of America through Providing Appropriate Tools Required to Intercept and Obstruct Terrorism. This act grants special new powers to U.S. law enforcement agencies so that they can hopefully prevent future terrorist attacks. With these new powers, the law enforcement agencies can encroach upon the privacy of the citizens of the U.S. and foreign visitors to the U.S. without public knowledge or justifiable cause.

These powers violate the fourth amendment of the U.S. Constitution, which guarantees the right of privacy. The question has become whether the special new powers granted by the USA PATRIOT Act to law enforcement agencies are necessary to protect our national security, or are law enforcement agencies using the terrorist attacks as an excuse to violate the privacy of individuals in order to solve criminal activities not related to terrorist acts.

The Fourth Amendment was passed into law as part of the Bill of Rights, which consists of the first ten amendments to the U.S. Constitution. Its meaning and intent stem from colonial resistance to the English system of warrants, or “writs of assistance” as they were referred to. First used in the American colonies in 1662, writs of assistance allowed English soldiers the authority to enter any home, at any time, and seize anything they deemed to be contraband or illegal in the eyes of the English law. They did not require the name of the person whose property was to be searched, the place being searched, or prior approval by any magistrate. Also, the writs remained in effect until the death of the king or queen under whom the writs were issued. This allowed the soldiers to return at anytime to the residence. The reasoning put forth by the British was that the writs were used to stop the vast network of smuggling in the colonies. The colonists hated the writs and, as John Adams predicted, the writs were “The commencement of the controversy between Great Britain and America.”

Much of the legal precedent for the Fourth Amendment was derived from the Paxton case in 1761. James Otis, Paxton’s lawyer, passionately denounced the writs in court as, “The worst instrument of arbitrary power, the most destructive of English liberty, and the fundamental principles of law, that ever was found in English law books.” He presented to the court a just form of a warrant, much like a modern warrant, in which the name of the person, the place to be searched, and the evidence to be gathered were all named so as to protect an individual’s liberty and right to privacy. Despite his strong legal argument, Otis lost the case, which in turn sparked great anger in the colonies and was one of the factors leading to the revolutionary war.

Mr. Otis’s oration… breathed into this nation the breath of life. [He] was a flame of fire! Every man of a crowded audience appeared to me to go away, as I did, ready to take arms against the Writs of Assistance. Then and there was the first scene of opposition to the arbitrary claims of Great Britain. Then and there the child of independence was born… [I]n 1776, he grew to manhood and declared himself free. - John Adams

In 1791, James Otis’ legal arguments concerning a citizen’s right to privacy were utilized by James Madison in drafting the Fourth Amendment. The text of the fourth amendment reads: “The right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures, shall not be violated, and no warrants shall issue, but upon probable cause, supported by oath or affirmation, and particularly describing the place to be searched, and the persons or things to be seized.” As stated by Richard J. Cretan, the Fourth Amendment…

…offers one of the greatest protections of individual liberty found in the U.S. Constitution. The amendment stands between the power of law enforcement and the right of citizens to be free from undue intrusion into their lives and property. It recognizes the government’s authority to conduct searches and make seizures of criminal evidence, as well as to issue warrants for arrest, search, or seizure. But these powers are curtailed by protections for citizens. The government is prohibited from unreasonable police actions and from issuing warrants without probable cause. Through its recognition of police authority restrained by guarantees of liberty, the amendment strikes a balance between the interests of a free society and the need for enforcement of laws.

When the Fourth Amendment was written, it was a very simple and strict form of protection for the people against the government. Illegal search and seizure was only applied to the physical private property of citizens of the U.S. The amendment’s protection was only available to a defendant in federal court cases. The first clause of the amendment, protection from illegal search and seizure, was just meant to protect the citizens from the government seizing private property. The second clause, probable cause for a warrant, was implemented only to make warrants necessary for a search and specific enough to protect from general warrants like the writs of assistance.

The Supreme Court’s interpretation of the Fourth Amendment has brought many expansions and changes to its powers since its inception in 1791. In Weeks vs. U.S in 1914, the court invented the exclusionary rule, which states that no evidence obtained in violation of a defendant’s Fourth Amendment rights by police is admissible at trial. The defendant, Freemont Weeks, filed a court motion for his property, which had been seized by state police and federal marshals without a warrant, to be returned to him. If the property was returned, it would not be available to the court for use as evidence. The Supreme Court ruled in favor of Weeks on the basis that the officers had violated the Fourth Amendment. Judge Rufus Day’s decision stated:

If letters and private documents can thus be seized and held and used in evidence against a citizen accused of an offense, the protection of the fourth amendment declaring his right to be secured against such seizures is of no value, and so far as those thus placed are concerned, might as well be stricken from the constitution. - Judge Rufus Day

This decision established the exclusionary rule. This rule could cause havoc in the cases against terrorists, which will come to trial as a result of evidence gathered under the USA PATRIOT Act. There are so many warrantless searches and even searches without probable cause allowed by the act that the court will be hard pressed to allow much of the evidence because the methods by which police obtain it violate the exclusionary rule.

The exclusionary rule’s power was originally intended to be used only in federal cases. However, its power was extended to the state level by Mapp vs. Ohio in 1961. Mapp’s house had been entered on the basis of a faulty warrant, and evidence seized had then been used in trial. The Supreme Court ruling, handed down by Justice Tom Clark, permanently extended the exclusionary rule to the states because the police involved were all of the state level. By judging in favor of Mapp, it required the states to follow the Fourth Amendment. In his judgement Justice Tom Clark explained the state refusal of the exclusionary rule as “The ignoble shortcut to conviction left open to the state tends to destroy the entire system of constitutional restraints on which the liberties of the people rest.” He also explained why the rule must apply even in a case in which the evidence leaves no doubt of conviction. “The criminal goes free, if he must, but it is the law that sets him free… [for] nothing can destroy a government more quickly than its failure to observe its own laws, or worse, its disregard of the charter of its own existence.”

This precedent means that all evidence seized, whether by state officials under new anti-terrorist state laws, or by federal agencies under the USA PATRIOT Act, is subject to the Fourth Amendment and its exclusionary rule.

The Supreme Court has also been required to apply the principles of the Fourth Amendment to new technologies which were not yet discovered in 1791. A case involving the use of new technology came to the court in Silverthorne Lumber Co. vs. US in 1920. The police illegally seized documents from the company and took photographs and copies of the documents. They then returned the evidence to the Silverthorne Company and used the photos and copies in the trial. In the ensuing case Justice Oliver Wendel Holmes delivered the court’s decision in favor of Silverthorne Lumber Co.’s motion to have the evidence suppressed.

The essence of a provision forbidding the acquisition of evidence in a certain way is that not merely evidence so acquired shall not be used before the court, but that it shall not be used at all. - Judge Oliver Wendell Holmes

The decision strengthened the exclusionary rule in that it forced law enforcement agencies to follow the rule in meaning as well as in wording. The evidence obtained is not unlike many of the computer programs the government uses to read, but not seize, e-mail and voicemail. If such a precedent holds up, much of the evidence gathered by these new methods could be suppressed under the exclusionary rule at trial.

Specific to the new powers of the federal government under the USA PATRIOT Act was the case Katz vs. US in 1967. Federal agents had used a wiretap to conduct surveillance of Katz while he was making calls from a public phone booth. The evidence was suppressed by the Supreme Court because of the interpretation of privacy. Privacy, as was judged, depends on the person, not the place. This created the reasonable privacy test, where as suppression of evidence depends on if the defendant is to expect a reasonable amount of privacy in the area from which the evidence is gathered. With regard to electronic surveillance, the court stated “searches conducted outside the judicial process, without prior approval by a magistrate or judge, are per se unreasonable under the Fourth Amendment.” This statement, along with the verdict, made it illegal to conduct any electronic surveillance without a warrant. The USA PATRIOT Act creates many different searches, types of surveillance, and types of seizures available to law enforcement without warrants, which may not hold up in court under the exclusionary rule.

Contrary to Katz, Terry vs. Ohio may present a legal precedent for limited searches without warrants. Its decision made legal the “stop and frisk” search, or a limited search of a suspect’s clothing for weapons by a pat down. The officer could stop and search a person who was acting suspiciously. Most importantly, it established that only suspicion was needed as grounds for a warrantless search, not probable cause. The Court found this as a balance between “two opposing interests – social order and individual freedom – and finding that, sometimes, the former requires some sacrifice of the latter.” The decision also lengthened the amount of time a warrantless search could be conducted. The court decreed that officers should follow “the principles of Terry” in using their judgement on how long a suspect could be detained for a suspected violation. These principles are applied to such searches as highway stops for suspicious driving, airport bomb sniffing dogs, and border crossing detainment for drug searches. This decision opens a loop-hole for many of electronic searches without warrants allowed by the USA PATRIOT Act, as they take literally no time to conduct and don’t detain people, just copy information.

The latest use of technology in a case involved thermal imaging in Kyllo vs. U.S. in 2001. The police used thermal imaging to confirm that Kyllo was growing marijuana in his house with hot lamps, and using that information gained a search warrant and found the marijuana. The court had to decide if using a device from outside Kyllo’s house was an unreasonable search. They deemed it to be a search as there was the “expectation of privacy” in his home, even though no physical entrance occurred. This can drastically effect the USA PATRIOT Act in that the searches of personal electronic information or “sneak and peak” warrantless physical searches allowed in the law could be supressed as violations of the fourth amendment in that there was a reasonable expectation of privacy.

Despite the last 200 years of case precedent which expanded the interpretation of the Fourth Amendment, the USA PATRIOT Act greatly expands the power of law enforcement and encroaches on those precedents. The act was passed through Congress with extreme haste, and debates on the act, which normally take place on the floors of the Senate and House of Representatives, proceeded behind closed doors and off the public record. The congressmen and senators were not even able to read the text of the act before it was brought to a vote. The passage from conception to law for the USA PATRIOT act was one of the shortest ever in American history. The new powers granted by the act which violate the fourth amendment include: presidential power to confiscate any property under U.S. jurisdiction of a non-citizen who plans or carries out an attack against the U.S.; all judicial review of this evidence may be classified and be presented only to a secret court; federal authorities may use, wire, oral, and electronic, taps and surveillance to produce evidence against those involved in plots with the threat of weapons of mass destruction or computer fraud; the government may direct or compel any person or institution to produce a person’s personal information who is subject to an investigation; greatly increased time periods on electronic surveillance of any non-U.S. citizen; subpoenas for electronic information now include length, type, and duration of logon and service used, temporary internet connection number, and means and source of payment (credit card numbers and bank accounts); Internet Service Providers (ISP’s) can be forced to produce any information they have on a person if it is for the protection of life and limb; the government can delay the notice to a person that they are the subject of a warranted search if disclosure of the search would have adverse effects on the investigation; the government can apply for a court order forcing businesses to produce records that are relevant to foreign intelligence and terrorism investigations; allows trap and trace devices, which track a persons electronic activity, to be used with a court order; trap and trace devices can trace all information pertaining to electronic communications except its content; all warrants issued for terrorism related activities extend nationwide; all warrants for electronic communication extend nationwide; U.S. law enforcement jurisdiction extend to any device outside the country owned or operated by a U.S. company which is used to harbor, transport , commit, or deliver a weapon that harms the U.S.; the attorney general can issue wiretaps without judicial consent; warrants, subpoenas, and court orders can be issued by a secret court which the public has no access to; the government can institute roving wiretaps where by anyone’s phone in the U.S. can be tapped.

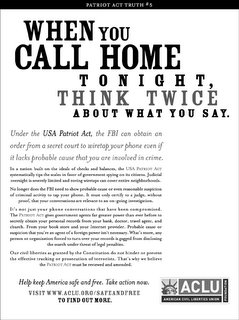

The public outcry against these questionable provisions in the USA PATRIOT Act has been vast. The biggest opponent of the act’s sweeping changes is the ACLU (American Civil Liberties Union). The ACLU has made many valid points about how the new powers of the government can be misused and abused to further propagate the ability of law enforcement to pry into people’s privacy. In a letter to congress protesting the new powers and encouraging the representatives to vote down the act, the ACLU made known their disagreements.

“[The act] gives the Attorney General and federal law enforcement unnecessary and permanent new powers to violate civil liberties that go far beyond the stated goal of fighting international terrorism. These new and unchecked powers could be used against American citizens who are not under criminal investigation, immigrants who are here within our borders legally, and also against those whose First Amendment activities are deemed to be threats to national security by the Attorney General.”

The ACLU also published many articles by various authors in protest to the USA PATRIOT Act. The authors compared the acts new expansive powers to McCarthyism and Red Scare politics of the 50’s and 60’s, and the new anti-terrorism units in law enforcement to the Red Squads who terrorized socialist organizations during the McCarthy era. They also believed that some of the new provisions would increase racial profiling among law enforcement and the American public. By using the new provisions, a person’s point of view on U.S. foreign policy and or political associations, formerly protected under law, might be used as evidence or probable cause to prosecute that person or hold them as a terrorist suspect. The ACLU authors also contended that the minimized role of the judiciary due to the new law would be extremely detrimental to the protection of privacy. They think the system skews the regulatory checks and balances between the police and the court which protect the citizens of the U.S. from police abuses.

Another organization which holds many of the anti-USA PATRIOT Act views of

the ACLU is the EFF (Electronic Frontier Foundation). The EFF compared the new powers of law enforcement to those used by the FBI in the 60’s and early 70’s to spy on such prominent civil rights leaders as Martin Luther King. The EFF also brought up the specific point of questioning whether the vast civil liberties our society enjoys were actually the problem and or cause that brought on the attacks.

The civil liberties of ordinary Americans have taken a tremendous blow with this law, especially the right to privacy in our online communications and activities. Yet there is no evidence that our previous civil liberties posed a barrier to the effective tracking or prosecution of terrorists. In fact, in asking for these broad new powers, the government made no showing that the previous powers of law enforcement and intelligence agencies to spy on US citizens were insufficient to allow them to investigate and prosecute acts of terrorism. The process leading to the passage of the bill did little to ease these concerns. To the contrary, they are amplified by the inclusion of so many provisions that, instead of aimed at terrorism, are aimed at nonviolent, domestic computer crime. In addition, although many of the provisions facially appear aimed at terrorism, the Government made no showing that the reasons they failed to detect the planning of the recent attacks or any other terrorist attacks were the civil liberties compromised with the passage of USA PATRIOT Act.

In addition to their questioning of the government’s intentions and actions, the EFF publicly solicited Congress to consider checking the powers granted in the act, including: making sure law enforcement agencies use the new powers carefully and only on cases of terrorist nature; punishing anyone in the government who missuses the new powers to spy on innocent people or violate their privacy under the guise of a terrorist investigation; refusing to allow evidence illegally obtained by using these new powers in a court of law in which a person not involved in terrorist activities is being tried; using the vague and undefined terms in the act, such as “content,” “without authority,” and “contractual,” justly and with intentions so as to serve the country and not the private interests of the government; making the government specify people and reasons for their “roving wiretaps” served to ISP’s and telephone companies; requiring a report on all actions and investigations done by the government using the new powers in 2005 when some of the law’s will sunset and need to be renewed by congress.

The CDT, Center for Democracy and Technology, also has specific concerns about the powers granted by the USA PATRIOT Act. Their argument against some of the new powers is the more moral issue of “If we give up the constitutional freedoms fundamental to our democratic way of life, then the terrorists will have won.” The believe that the freedoms enjoyed by the country in communications before the new powers are a way to fight the terrorists, and more importantly are what make out country great. The CTD believes “surrendering freedom will not purchase security, democratic values are strengths, not weaknesses, [and] open communications networks are a positive force in the fight against violence and intolerance.” They compared the new fear of terrorism to the underlying motivation the country had during World War II when the alien and sedition acts were passed. These acts put thousands of Asian people in camps so as to protect liberty and democracy when they had done nothing at all. One of their specific restrictive fears is that the government will curtail free speech on the internet and internet activity itself in the name of

fighting terrorism and preserving liberty.

The Internet is the people's voice. As demonstrated in the last few days, it was the open Internet that allowed people to contact and reassure their loved ones and to give vent to their feelings. Those are positive benefits of the openness and innovation of modern communications technologies. Moreover, building government surveillance features into communications networks can reduce security and create new risks of vulnerability. Nor is there anything to be gained by limiting freedom of expression. Pushing dissenting voices off the Internet does not increase security.

The only public proponents of the USA PATRIOT Act are a few key officials in the U.S. government. Most government officials have not commented on the act at all because there were no public deliberations on the act, no politics to delay the act from passing, and no Republican versus Democratic party mud slinging to bring to light weakness or strength in the act. Everything was done in secret and behind closed doors. The most noteworthy vocal supporters of the act were Attorney General John Ashcroft and President George W. Bush.

Ashcroft is enamored with the new powers under the USA PATRIOT Act, and often speaks about “use[ing] a single court order to trace a communication even when it travels outside the judicial district in which the order was issued.” Ashcroft deems his new powers necessary because “In order to prevent terrorism… law enforcement must be able to intercept communications between terrorist leaders and soldiers,” and “increased efficiency saves vital time during investigations and bolsters the nation’s ability to detect coordinated conspiracies.”

President George W. Bush’s speech announcing the USA PATRIOT Act gave his reasons for signing it. He believes that the Act was completely necessary to prevent any more such acts as that occurred on 9/11/01. He refers to the terrorists as people who will stop at nothing to hurt and destroy the U.S., and so he declared “These terrorists must be pursued; they must be defeated; and they must be brought to justice. And that is the purpose of this legislation… The bill before me takes account of the new realities and dangers posed by modern terrorists. It will help law enforcement to identify, to dismantle, to disrupt, and to punish terrorists before they strike.” He also believes that the Act passed so quickly though congress because “it upholds and respects the civil liberties guaranteed by our Constitution.”

The vast majority of public opinion seems to be against the USA PATRIOT Act and yet for it at the same time. The nation wants its civil liberties but at the same time doesn’t want another terrorist attack to happen ever again. Public opponents of the act make it seem as though the government intends to strip us of our liberties by using the attacks as an excuse. This is an unproven concern. In 1998, with the existing wire tap laws, only 1,329 orders were issued. 72% of those wiretaps were for drug traffic related cases. In every single case in which the wiretaps were used as evidence, there was sufficient probable cause found for their use.

The United States of America is a democratic republic, meaning “a government for the people, by the people, and of the people.” The U.S. government is trying to act in the best interests of the country and to protect the people for which it is created. Weapons of mass destruction such as nuclear bombs or biological and chemical weapons did not exist in the times of Washington, Jefferson, and Adams. The fourth amendment should not be used to protect terrorists who would harm this country and its citizens with such awesome and terrible weapons. I seriously doubt that James Madison would ever want his amendments to protect people who would sacrifice themselves in the name of a religion to kill thousands or millions of American citizens. In a time of war, some civil liberties must be lawfully and responsibly curtailed in order to endure the safety of the country.

It is also important to recognize that advanced forms of electronic telecommunications and the internet did not exist when the Fourth Amendment was written or even when the court interpretations of it were handed down. The technology available today is so advanced compared to the times of the founding fathers that new exceptions need to be made to the Fourth Amendment. If terrorists are allowed to use technology to plan their attacks, and then use the freedoms this country provides as protection, then the survival of our country is at risk. Law enforcement needs to have access to the same level of technology that terrorists do, and be able to use such technology freely to stop terrorist attacks. A key issue that needs to be watched closely is that the new powers granted by the USA PATRIOT Act may not be effective if the terrorists have access to encryption devices. These devices electronically scramble messages and make it almost impossible for law enforcement to decode the messages. If the terrorists regularly use these encryption devices, then the new powers granted by the USA PATRIOT Act would be moot. This is one of the key issues that needs to be addressed before the USA PATRIOT Act is renewed and extended in 2004.

The last time that our country faced such a serious threat to our security and safety was in World War II when the Japanese made a surprise attack on our country and killed thousands of our soldiers at Pearl Harbor. This resulted in a long and deadly war which killed thousands of people on both sides of the conflict and did not end until two atomic bombs were dropped, killing thousands of Japanese citizens. If the U.S. Government had the expanded powers provided by the USA PATRIOT Act back then, the U.S. intelligence community could potentially have intercepted messages pertaining to the attack on Pearl Harbor, and prevented some of the terrible loss of life that subsequently occurred. It may have also avoided the use of nuclear weapons to end that war. In my opinion, it is worth giving the government these expanded powers on a test basis through 2004 to try to prevent the loss of millions of lives. The potential destruction of our country from nuclear or biological weapons is a constant threat. The question remains whether these expanded powers will enable our law enforcement agencies to protect our country from such horrendous attacks.

Bibliography

1) Adam Cohen, “Rough Justice: The Attorney General has powerful new tools to fight terrorism. Has he gone too far?” Time December 10, 2001: 30.

2) Bart Kosko, Times Mirror Company; Los Angeles Times 2001, 2 December 2001: M.5

3) Barton Aronson New Technologies and the Fourth Amendment: The Trouble With Defining A "Reasonable Expectation Of Privacy"

4) CDT Statement Preserving Democratic Freedoms in Times of Peril, http://www.cdt.org/security/010914cdtstatement.shtml

5) EFF Analysis of the Provisions of the USA PATRIOT Act, http://www.eff.org/privacy/surveillance/

terrorism_militias/20011031_eff_usa_patriot_analysis.html

6) George W. Bush, “Remarks on Signing the USA PATRIOT Act of 2001”, 26 October 2001

7) How the USA-PATRIOT Act Allows for Detention and Deportation of People Engaging in Innocent Associational Activity. http://www.aclu.org/congress/110230lh.html

11) Jim McGee, “Fighting Terror with Databases,” Washington Post, 16 February 2002: A27

12) Laura W. Murphy and Gregory T. Nojeim, Be Patriotic – Vote Against the Revised “Patriot Bill”, http://www.aclu.org/congress/l101201a.html

13) Richard J. Cretan, “Fourth Amendment,” Constitutional Amendments: 1789 to the Present, ed. Kris E. Palmer (Gale Group: Detroit, 2000) 67.

14) “USTA: Industry is ‘Best Partner’ in Govt. Surveillance Efforts”, Communications Daily, 4 March 2002